Can data cooperatives clinch digitalization benefits for farmers?

On agricultural data cooperatives and where the data economy meets the solidarity economy.

There is an increasing clamor in digital agriculture and data governance circles to ensure that the economic benefits of digitalization and data in agriculture reach farmers. Last month, I wrote about how digital market coordination, away from the more simplistic notion of market access for farmers, could be part of the answer that leverages the platform economy1. Farmer-centric data governance is at the core of an emerging paradigm shift to ensure fair distribution of digitalization benefits. Data cooperatives are among the many data governance models proposed to advance this paradigm shift. We may define a data cooperative as:-

“a member owned, democratically governed organization facilitating the pooling of members’ data for mutual economic, social, and cultural benefit.”

Although this article explores the viability of data cooperatives for delivering digitalization benefits to farmers, it should first help to set the context on agricultural data and the surrounding power dynamics.

Agricultural data as an invisible goldmine

Handwritten logs and manual input to devices offline or online are viable agricultural data sources, especially among smallholder farmers in the Global South. Crop and animal production data can also be collected via earth observation techniques such as imagery from satellite and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). On-farm tools and equipment are also a growing source of agriculture production data. Such data includes readings from equipment sensors and UAV operations via machine-to-machine (M2M) interfaces or as part of the Internet of Things (IoT). For livestock, the sensors may include boluses and infrared tags on animals. On-farm data could relate to soil, water, plant or animal health, weather, inputs, yield, farm financials and admin, and field operations.

Studies estimate that the average farm generates as many as 500,000 data points daily23. Agricultural research organizations such as ILRI can achieve quantum-leap acceleration in their development goals if they institute mechanisms to crowd-source and use data from live production in farms while respecting farmers’ data sovereignty. The data richness in agricultural production should ideally contribute to improving farmers' social and economic bottom line, but such is not always the case for non-obvious reasons. Firstly, much of the data is not captured, processed, or analyzed to give farmers actionable insights. Secondly, although digital agriculture providers may build on the data to tweak their offerings, farmers hardly ever access the macro-level insights and data aggregated across their peers for their decision-making. Thirdly and more cynically, digital agriculture providers may willingly or inadvertently expose farmers’ or farming data to exploitation internally or through third-party access.

To respect the complexity of agricultural data, I’d argue that not only production-related data should benefit farmers. Data relating to the transformation of agricultural produce downstream in the value chain should be harnessed to improve the economic bottom line for farmers and other rural actors. This includes logistics, agro-processing, trade, and consumption data. But it helps to understand which entities control or own all this data.

Digital Agriculture Providers are in control - No?

Though a young field, digital agriculture has already experienced a history of data breaches and controversies. As digital agriculture providers independently digitalize on-farm and off-farm operations, as implied in their business models, they become custodians of large amounts of data if their solutions achieve significant uptake. Many of these AgTechs, as they are also called, may not have the capacity or interest to analyze all the data they accumulate. Among the solution providers in a digital agriculture ecosystem, data-level collaboration to unlock sector-wide benefits remains impeded by the absence of goodwill or enabling data governance frameworks. Such gaps suggest systemic inefficiency, where sectoral data collection investments are not followed through with appropriate analytics to actualize and distribute the returns to the AgTechs and, more so, to farmers. As such, such sector-wide inefficiency takes the farmers’ data altruism for granted.

A data-sharing partnership between Bayer FieldView and Tillable was only short-lived after suffering significant controversy. Farmers using Tillable were meant to easily share data about their operation with FieldView and build their reputation for increased assurance to landowners that their property was adequately cared for. Australian hacker “Sick Codes” presented a jailbreak4 for John Deere tractors, taking control of multiple tractor models through tractor touchscreens, possibly advancing the clamor for farmers’ right to repair their equipment. Quite demonstrably, digital agriculture providers may not always guarantee basic data protections, let alone the distribution of economic benefits of digitalization and data to farmers. More cynically, as Australian farmer Dough Smith decries in an interview4, the agricultural data initiatives may stumble into the darker side of exploiting farmers through their data.

“There is an assumption out there that farmers are not very good at what they are doing … farmers today are very good businessmen … the collection of data and the aggregation of data, … is all about farming the farmer, not farming the farm”. ~ Doug Smith, farmer and Chairman of Australian Grower Group WA Grains

A data economy begets data politics

While advocating for a farmer-centric paradigm for agricultural data governance5, a 2023 report commissioned by USAID and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation highlights farmers’ dilemma on protecting versus sharing their data. The report attributes this dilemma to farmers’ capacity and data governance challenges. The report notes;

“… While the use of data holds much potential to strengthen the agriculture sector, farmer capacity and data governance challenges raise the possibility that farmers will not benefit economically from their data.”

Recently, the Commonwealth Secretariat has vigorously advocated for better management of agricultural data6 as digital public infrastructure, pitching such management as a matter of national sovereignty. From this perspective, the ownership and control of agricultural data should be nationalized for efficient harnessing as a national resource. The case for national-level efficiency toward food security and optimized economic stewardship is difficult to argue against. The Commonwealth article observes;

“… member states need to consider agricultural data in their countries as a national resource and take the necessary policy actions to guard the resource and maximise the potential of the data for its citizens and across the entire Commonwealth.”

-driven mechanisms. The approach could quickly progress to expropriating data from service providers and their users across value chain stages, including farmers. As valid and socially sound as it may be, such data expropriation may also raise questions about the power dynamics currently associated with data held by digital agriculture providers on their way to becoming part of Big Tech7.

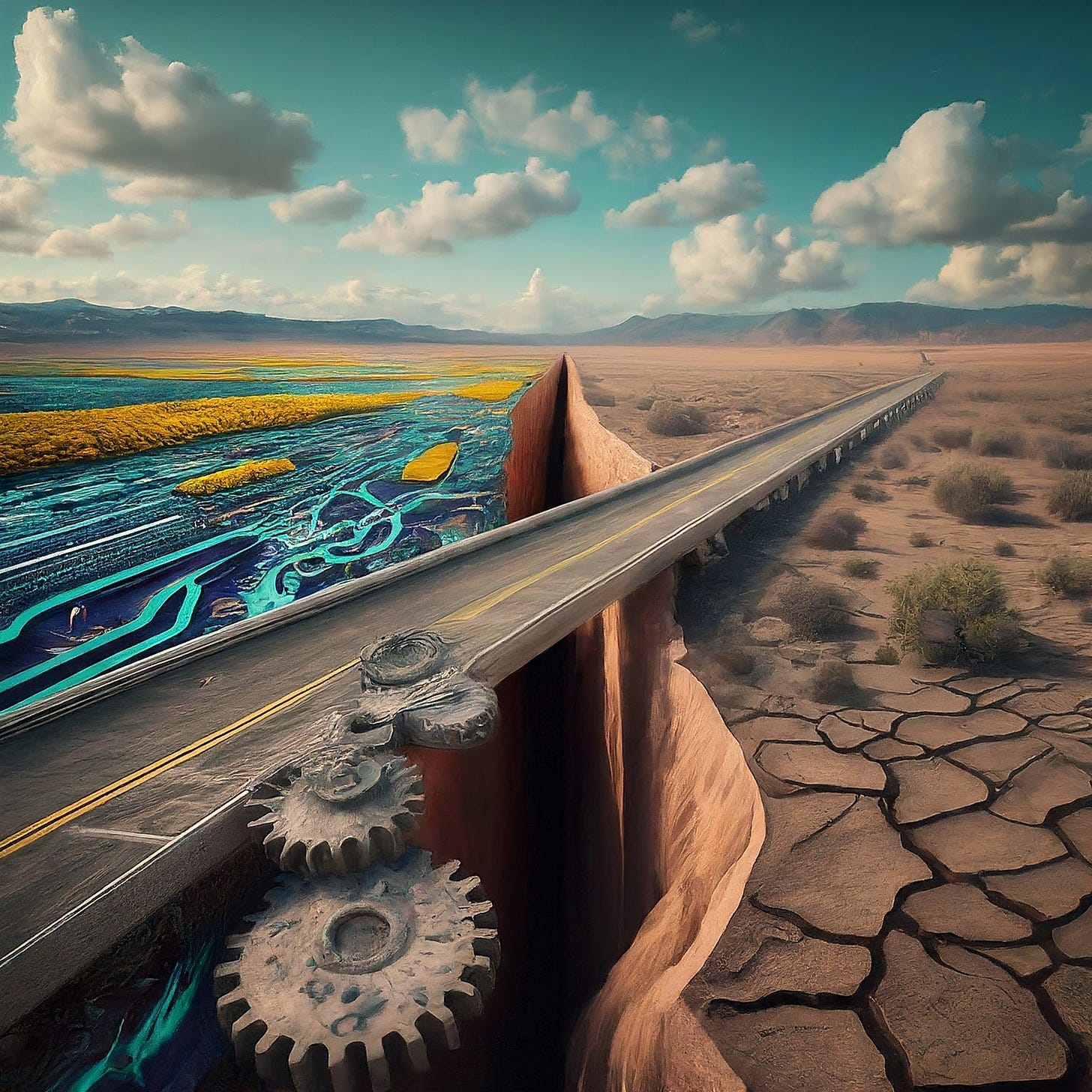

Data economy meet the solidarity economy

Can farmers and other rural actors in the Global South rest assured that increased nationalization of agriculture data does not also carry along legacy elements of elite capture that have haunted the sector? What if one argues that Government officials in the Global South have traditionally watched over the elite capture, which they may propagate more easily, thanks to the increased nationalization of sectoral data? Large corporations in big tech, farm equipment or input companies, and the food and beverage giants are just an AgTech Startup away from agricultural data. This is if such powerful cooperations are not directly handling or contributing to agricultural data. It is challenging to find assurances that these corporations will genuinely contribute to the common good as they pursue profit with the sectoral data landing in their data clouds.

Farmers and rural actors are caught between the interests of profit-seeking corporations, corruption-vulnerable government officials, and indifferent development agencies. They should maximize their economic benefits from agricultural data in ways less reliant on the goodwill of service providers, governments, and development organizations. The unity and collaboration expected to actualize through cooperatives for the collective pursuit of such benefits is a natural advancement of this discourse.

Individual farmers or institutions can join agricultural data cooperatives. Initiatives like JoinData in the Netherlands and the Growers Information Service Cooperation (GISC) in the US have seen the emergence of purpose-built data cooperatives. Startups have also been argued to acquire the semblance of data cooperatives, as with the case of Artemis (formerly Agrylis) in Canada. Agricultural Data cooperatives have also emerged from partnerships between traditional agricultural cooperatives and data stakeholders. An example is the Illinois Corn Growers Association (ICGA) case with the University of Illinois and NASA giving birth to a Farmer Data Cooperative8. The National Cooperative Dairy Herd Improvement Program (NCDHIP) is an excellent example of how a collaborating mix of individual and institutional stakeholders can successfully advance data sovereignty as a data cooperative for decades9.

The promise of cooperatives as mechanisms for human development is old and has remained alive for decades. The European Union-funded #coop4dev initiative maps out the intensity of the solidarity economy, showing thousands of cooperatives and millions of members in most countries. An exciting prospect for farmer-centric data governance is legacy agricultural cooperatives augmenting their value proposition by spinning off, if not evolving into, data cooperatives. Sharing this thought resulted in interesting reactions to a LinkedIn thread. In the thread, practitioners in my network strongly decried farmer participation in cooperative governance was very low (hence low trust levels, at least in Kenya). At the same time, this thinking appeared to present an opportunity to increase the localization of impact among development agencies, according to the responses.

Viability of agricultural data cooperatives

Below are crucial questions for clarifying how data cooperatives, whether existing or new purpose-built cooperatives, can increase farmer-centric data governance.

Are there agricultural value chains where data cooperatives are comparatively more straightforward to thrive?

Can agricultural cooperatives in the Global South overcome the hurdles of participatory governance and trust to genuinely serve as data cooperatives? How can such data cooperatives be immunized from elite capture?

Which is more efficient: Enhancing legacy cooperatives to take data cooperative roles or creating new purpose-built agricultural data cooperatives?

Can data cooperatives be entrusted with ensuring their member farmers can make the most of their data and the insights derived with data aggregation and value transformation downstream? Can they address any capacity gaps found among small-scale farmers?

What degree of fragmentation or factionalism among data cooperatives is ideal for unlocking economies of scale and scope? Consider farmer diversity along geographical scope, value chain focus, production scale (small scale vs. large scale), and production types (e.g., organic, regenerative).

The above questions and the article, in general, have benefited from the generous input of friends and fellow practitioners Jennifer Volk - Senior Information and Data Systems Lead, and Angela Ndaka - Critical AI Scholar and AI Ethicist.

Which other concerns need answers to justify investing more in data cooperatives as a model for farmer-centric data governance in Agriculture, especially in the Global South? Please share your thoughts in the comments section below.

excellent summary of the opportunity. USAID's Cooperative Development Project should be able to help with governance and the cooperative operating environment. Please feel free to reach out at chammerdorfer@ncba.coop.

You raise important issues. It has been clear to me for a long time that agriculture has an acute governance problem both in the public and in the private (cooperatives and other intermediaries) sectors. We can't pursue a digital agriculture agenda whilst avoiding the governance question; the latter of course is not palatable for the AgTech sector. That said, I strongly believe that trust remains a high value currency in agriculture at the local level and I also believe there continues to exist a real digital divide.

Therefore creating a new form of cooperative (a data cooperative) with a vocabulary and outlook that is most certainly 'alien' to many may not present as valuable a proposition for a farmer as a legacy cooperative with data cooperative capabilities. The incentives for many farmers, who don't see how their data could possibly be monetized, would be easier to craft through the traditional cooperative engagements with data ecosystem actors and collaboration with other agriculture sector ecosystem actors. They already do this to get better prices on inputs, better off take terms, affordable support services and lobbying of public sector institutions such as parliaments. A purpose-built cooperative should be a last resort in specific cases within geographies or value chains but the default should be legacy ones with data co-op superpowers.